Australian renewables is booming, but for how long?

2017 was a record year for renewable energy investment in Australia, but is it realistic to assume that this success will continue?

Director at K2 Management, Maria Cahill, looks at the investment drivers for renewable energy in the Australia’s market and how these will affect the longer-term commitment to clean energy development.

The dominance of coal

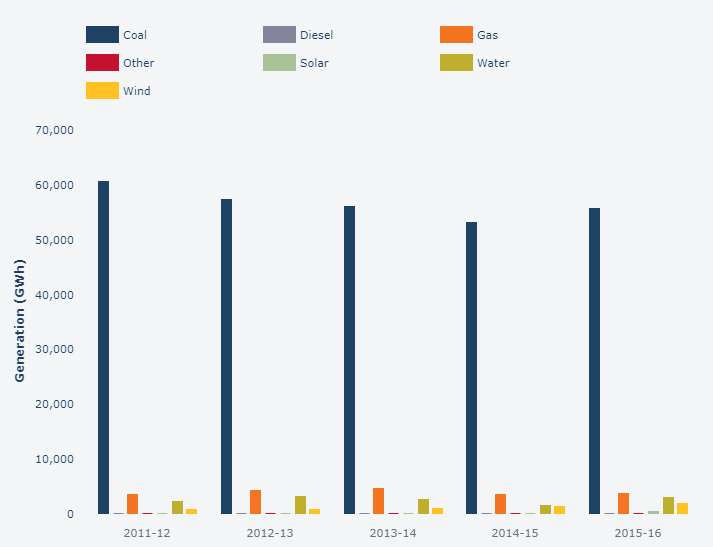

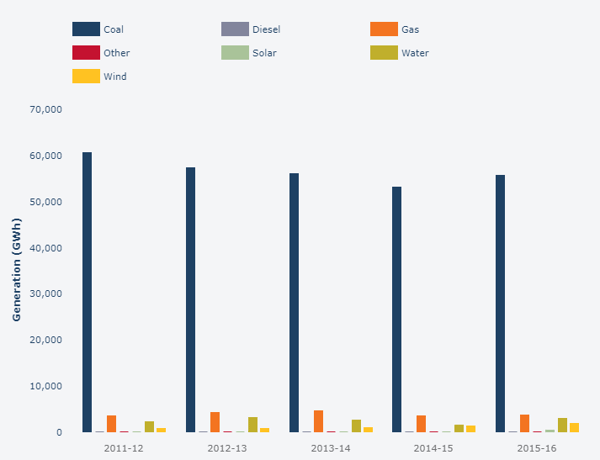

A large proportion of the energy requirement of most Australian states is met by coal fired power stations and it is clear from Fig 1 that coal is dominant across the country. When you consider this alongside the average age of the coal fleet, seen in Fig 2, and that most coal plants are decommissioned after 35 years of operation, it is evident that a contingency plan is needed to secure the nation’s energy needs.

Fig 1. Generation by fuel type in NSW (representative of most states in Australia)

Source: Aemo

Wholesale electricity pricing – stability required

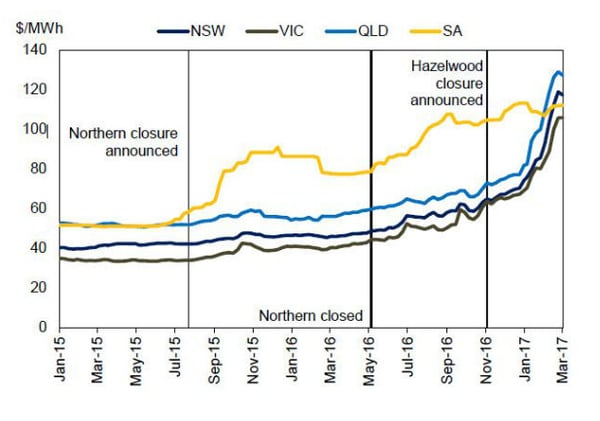

The price of electricity has more than doubled in most Australian states over the last 24 months and this trend appears to be set to continue at least in the short to medium term. Each news article announcing another coal plant closure, prompts a corresponding price spike in the wholesale power price.

While the federal government applies pressure to resistant utilities mandating them to invest in new coal plants, many State governments, are taking the opposite approach by setting their own renewable energy targets. Meanwhile home-owners seek to manage domestic bills by installing roof top solar and storage, while large industrial energy users look to anchor their cost base through securing corporate PPAs or by installing ‘behind the meter’ generation.

Fig 2. Impact on electricity prices due to Hazelwood closure (source: Bloomberg)

The federal renewable energy target

In 2015, the Australian government set the target to generate 33,000GWh of renewable energy in 2020. This bilateral commitment by the two main parties provided the certainty the sector needed and has led to record investment in recent years. It is expected that this target will be met through the build out of committed projects over the next 18 months. But what will follow beyond 2020 to drive investment beyond this target? How the government reacts may have a significant impact on Australia’s energy future beyond 2020.

Lack of policy could harm growth

Despite extreme energy price volatility and occasional state-wide black-outs, Australia is yet to set a clear energy policy. Renewable energy implementation remains a contentious issue as it is portrayed by some as causing grid instability, unemployment and energy price increases. Despite Australia committing to further carbon reduction targets when it became a signatory to the Paris climate accord and the subsequent recommendations set out by Finkel, the government’s chief scientist, in his 2016 report, the case for continued investment is far from water-tight.

Despite extreme energy price volatility and occasional state-wide black-outs, Australia is yet to set a clear energy policy. Renewable energy implementation remains a contentious issue as it is portrayed by some as causing grid instability, unemployment and energy price increases. Despite Australia committing to further carbon reduction targets when it became a signatory to the Paris climate accord and the subsequent recommendations set out by Finkel, the government’s chief scientist, in his 2016 report, the case for continued investment is far from water-tight.

Last year the federal government proposed the National Energy Guarantee (NEG) as a replacement for the RET. The NEG seeks to address three aspects of energy policy; security, reliability and affordability, however it has received a mixed response especially from pro-renewable Labour States and is yet to be endorsed. So where does that leave us?

In the absence of clear energy policy at federal level, States are setting their own renewables targets. Both Victoria and Queensland will run state-backed reverse auction schemes in 2018, which in aggregate will equate to 1GW of wind and solar deployment. Certain utilities are pre-warning of coal plant closures and pushing back hard against the federal government’s request that they extend operation of aging assets. Instead they are seeking to invest in wind, solar, storage and pumped hydro. The Tesla big battery (aka Hornsdale Power Reserve) installed in Dec 2017 and two more sizeable batteries, recently announced in Victoria, have positioned Australia as a global front-runner for storage implementation.

What does this mean for investors?

While abundant wind, solar and land resource makes Australia an ideal candidate for renewable energy project implementation, there remains a host of challenges for investors and developers. Lenders are still not prepared to fully finance merchant generation, so securing a PPA is critical.

It is understood that the recent VRET auction was heavily oversubscribed which raises a question about what will become of those projects that aren’t successful when results are announced in July. Many will seek a corporate PPA, but, while a number of corporate deals have been done in the last 12 months by large energy users such as Telstra, NAB, ANZ, Coca Cola and various universities, each agreement is bespoke, creating a barrier to mass application.

Grid constraint and marginal loss factors can further complicate project financial models, by adding additional revenue uncertainty.

Despite a significant number of 100MW+ investment opportunities, which represents an attractive ticket size for many large investors, long term revenue certainty remains elusive for many proposed projects. The Australian renewable market favours sellers who have already secured a PPA and those vertically integrated developers with access to the retail market.

What else are we seeing in the market?

Cost reduction is likely to come in various forms. Both solar and wind OEMs are looking for market share, creating competition at project procurement stage. Likewise European EPC contractors with considerable experience of project construction are establishing themselves in Australia and increasing the competition for local incumbents.

Cost reduction is likely to come in various forms. Both solar and wind OEMs are looking for market share, creating competition at project procurement stage. Likewise European EPC contractors with considerable experience of project construction are establishing themselves in Australia and increasing the competition for local incumbents.

While most wind and solar plants are currently built under a single EPC contract, as lenders get more comfortable with construction risk, it is foreseeable that contracts will be split between 2 or more parties, with a resultant reduction in risk premium.

There is still considerable headroom in terms of wind and solar technology. Increasingly large turbines at higher hub heights are being proposed, while a number of solar module suppliers are priming the Australian market for the roll out of bifacial technology. Innovations such as these, in combination with local economies of scale, should see downward pressure on project costs.

What does the future hold?

Although there remains a fear that Australia is at risk of another ‘boom and bust’ scenario as the details of the NEG are thrashed out; generally, there is a feeling that the market here has a new unstoppable momentum. This is borne out by the growing interest in Australian renewable energy projects from European and Asian investors.

The problems of spiraling energy costs, the aging coal fleet and climate change need to be addressed and if cost reductions continue to be realized, renewable energy and storage may well be the combined solution to Australia’s energy challenges.

Get in touch with Maria Cahill to find out more.